When Schools Become Targets: Ukrainian Documentary TIMESTAMP Screens at BAFTA

Nov. 26, 2025

London

From the first minutes of the screening, the room was silent; by the final scenes, many were wiping away tears, and the audience burst into long applause.

Opening the discussion, moderator Stephanie Baker shared her personal reaction to the film:

“As a journalist and a mother, I found it gut wrenching to watch Timestamp. It was a powerful film about an under-reported aspect of the brutal war in Ukraine — how a generation of children are struggling for their basic right to an education.”

Directed by Berlinale Crystal Bear winner Kateryna Gornostai and executive-produced by Osvitoria, Ukraine’s leading educational NGO, TIMESTAMP has already been showcased at EXPO 2025 in Japan and at the 80th United Nations General Assembly. The London screening marked another key moment in its international dialogue about education and childhood during war.

The panel discussion at the London screening of TIMESTAMP including Rob Williams CEO of War Child (seated second from left)

Photo: Anna Nekrasova

Opening the substantive part of the discussion, Zoya Lytvyn, founder of Osvitoria and executive producer of the film, spoke about the unprecedented scale of Ukraine’s educational challenge and the deliberate nature of attacks on schools:

“The case of Ukraine is unique. We are the first country in modern history to fully restart and sustain a nationwide education system during a full-scale war for nearly four million schoolchildren. We had no precedent to learn from, no existing model to rely on. We work closely with international organisations such as the UN, UNICEF, and the OECD, and they asked us to document how this process is unfolding in real time. At the same time, nearly 400,000 Ukrainian children still do not have access to in-person education. It is not where we want to be, but it is the best that can be achieved under the circumstances.”

She also emphasised the systematic destruction of the education system:

“Every seventh school in Ukraine has been damaged as a result of Russian aggression, a level of destruction worse than during the Second World War. We do not believe this is a coincidence. Education is a deliberate target, and education must be protected by all means. Long-term, meaningful cooperation and recovery projects in education must be a priority, because education is the foundation of a normal, peaceful life.”

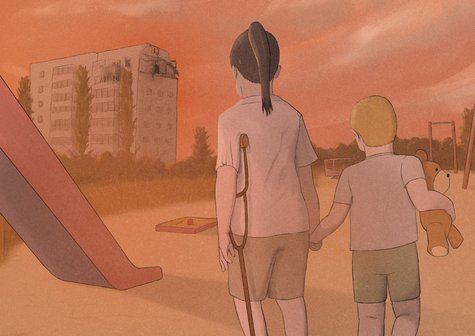

A still from TIMESTAMP

Photo: Oleksandr Roshchyn

Responding to this, Christina Lamb shared what she had personally witnessed while reporting from Ukraine:

“As a journalist covering conflicts, I have seen in Syria, Afghanistan, and Ukraine that schools are repeatedly targeted. After Bucha and Irpin were liberated, I visited a school in Irpin that had just been rebuilt after a missile struck its roof. During my visit, the air-raid siren went off, and I watched the children take their small backpacks and go straight down to the shelter. I went with them. I was speaking to their teacher when she began to cry. Her greatest fear, she told me, was that these children would grow up hating. She said she did not want that for them. This is how war shapes the everyday lives of ordinary people.”

Producer Olga Bregman then spoke about the ethical responsibility of documenting children’s lives during war and the creative choices behind the film:

“You won’t see the war directly in the film, instead, you’ll see how people reflect on it through the stories of how the lives of Ukrainian children, teachers, and the entire education community have changed. It was a deliberate choice to focus on how the war reshapes ordinary moments: classes, school breaks, and graduation celebrations. We filmed in different parts of the country, and although much of the material didn’t make it into the final cut, the fragments that remain often speak louder than any explicit scenes. When a student has to attend her prom online because her school in Bakhmut no longer physically exists, that single moment tells more than any direct depiction of violence ever could.”

A still from TIMESTAMP showing a destroyed school

Photo: Oleksandr Roshchyn

The most emotional response of the evening came during the remarks of teacher Nataliia Hutaruk, who described the realities of teaching thirty kilometres from the frontline and the determination of her students to keep learning:

“The special bond between children and teachers shown in the film is a direct result of the war. For many children, teachers have become the only stable adults in their lives, as parents are exhausted, serving in the army, or emotionally drained by loss. After years of online learning due to COVID and the war, students are now relearning how to communicate and how to be part of a real community. Children seek more emotional support from teachers, and we try to give it to them every day. In the underground school where I teach, a sign on the door reads ‘A Safe Space.’ It means not only physical shelter, but a place where children feel seen, accepted, and protected from the reality of war.”

Johanna Baxter, MP, spoke about her visit to Ukraine and the systematic nature of crimes against children:

"As a member of Parliament, I've visited Ukraine a number of times now and I have been very struck by what is happening to the children, and particularly the children that have been stolen by Russia. Whilst the official figure is 19546 children stolen by Russia we know that the real number is probably double that. In addition we know there are 1.6 million children in the occupied territories that are subject to militarization and indoctrination.

The thing that really struck me is the systematic nature of the attack on children by Russia. This is planned — children are being taken to 400 different locations across Russia and there are around 200 military camps that attempt to turn Ukrainian children into Russian soldiers."

The audience at the screening of TIMESTAMP in London

Photo: Anna Nekrasova

This visit resulted in an extensive report that Johanna co-authored with UK Friends of Ukraine which provides data and the timeline outlining how the children have been from abduction and the steps the UK Government can take to help their safe return, support their rehabilitation and hold Russia accountable for their war crimes.

The UK has also agreed a hundred year partnership with the Ukrainian government which not only commits military and humanitarian support but also commits both parties to strengthen cultural and social ties.

Speaking about what the world can learn from Ukraine’s experience, Rob Williams, Chief Executive of War Child Alliance, said:

"The big learning [from Ukraine's experience] is what happens when the government continues its commitment to education even though you might think that every resource would go to the fight, the struggle. Ukraine understood from day one that the real story for children is about their education, and Ukraine's achieved so much by keeping every child connected to some form of education. What you can see in the film, there is no place where creativity and innovation can't solve problems around education, and Osvitoria's been a huge part of helping to adapt to those really horrific circumstances."

The event was organised in partnership with TalentedU, an NGO supporting Ukraine’s cinema professionals in the UK, with the support of the Embassy of Ukraine in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Ukrainian Institute London.

The screening also highlighted the ongoing work of Osvitoria, one of Ukraine’s leading educational organisations. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Osvitoria has supported the restoration of more than 60 schools, maintained digital learning solutions for over 1 million users, trained more than 150,000 teachers, and developed crisis-response programmes to ensure no child is left behind. In 2025, Osvitoria also signed a memorandum with Cambridge University Press & Assessment.